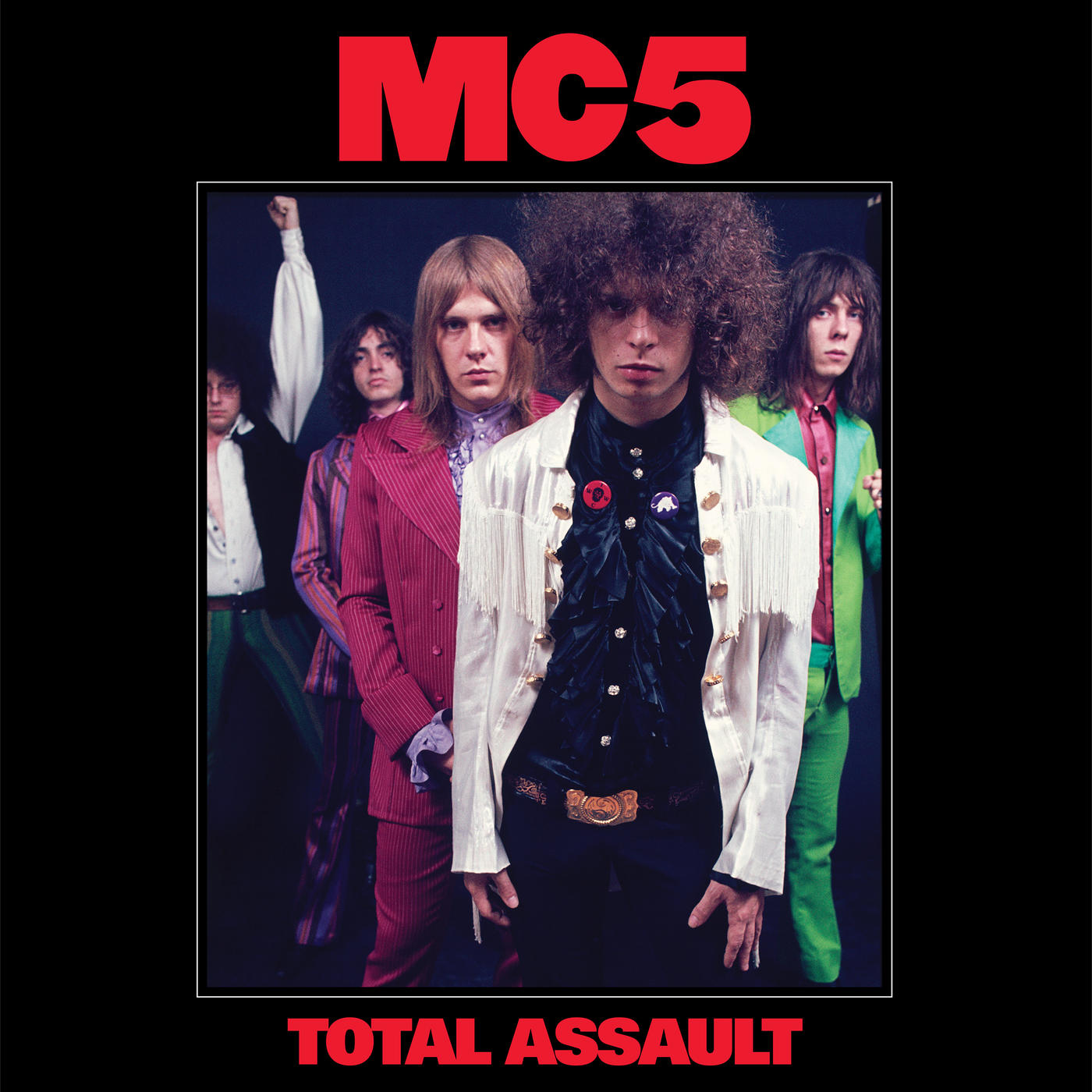

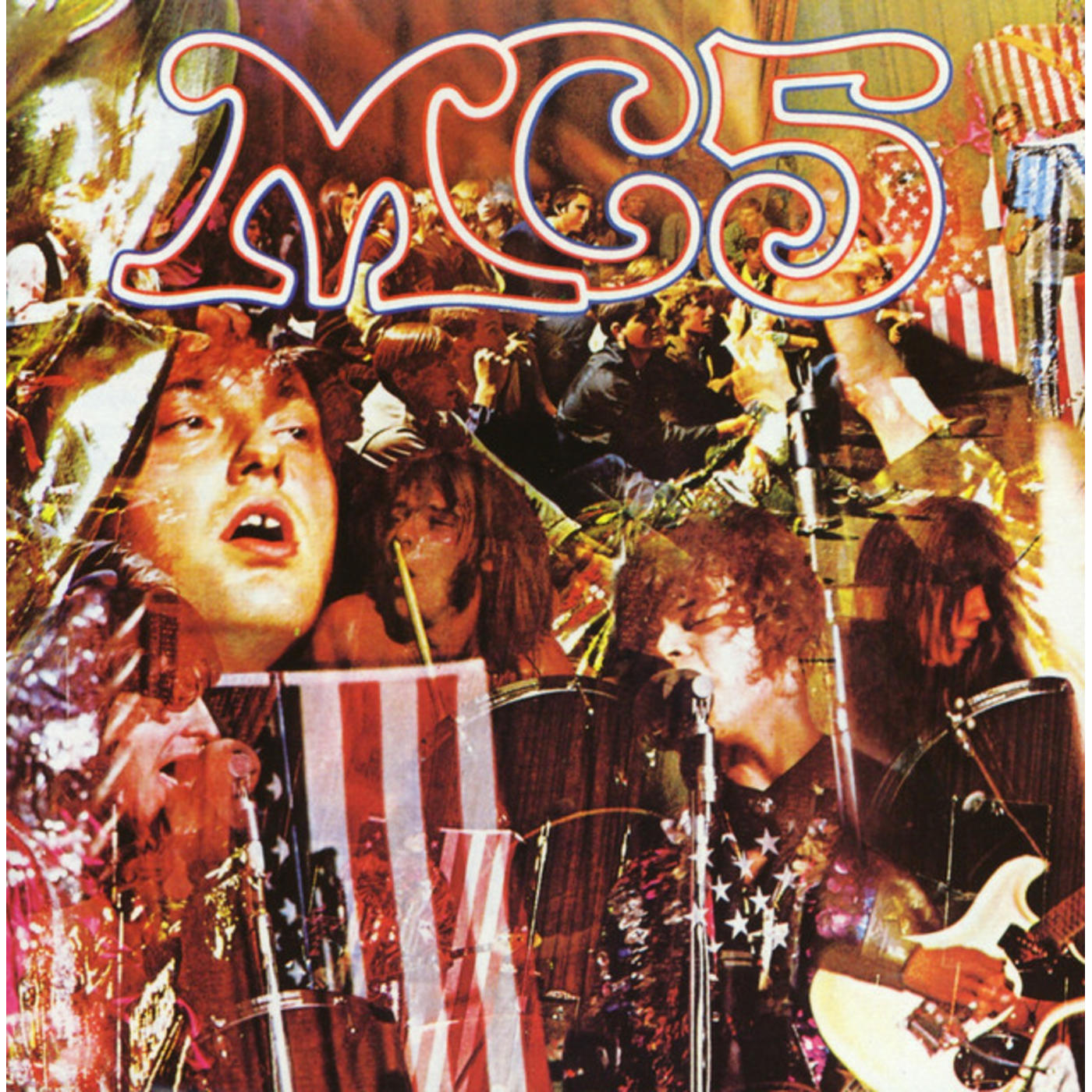

Interview: Wayne Kramer (The MC5)

Photo © Raeanne Rubenstein

by Will Harris

There’s no hyperbole in saying that The MC5 were one of the most important bands to emerge from America during the 1960s, which is why it’s so great that Wayne Kramer, one of the founding members of the band, decided to sit down and write himself a memoir. Mind you, he didn’t sit right down and write it. In fact, it took a fair amount of prodding for a fair while to finally get him to do the deed. Once he set his mind to it, the end result – The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, the MC5, and My Life of Impossibilities – turned out spectacularly. Kramer took some time to chat with Rhino about The MC5 as well as some of his post-band collaborators, including Johnny Thunders, Lemmy, and…Adam McKay? Yep: true story.

RHINO: Might as well kick things off with an obligatory question to ask anyone who’s just written a memoir: “What made you decide to write it?”

WAYNE KRAMER: Well, time was one reason. My friends had been bugging me for years to write a book, but I never had an ending, because I never felt like I was anywhere near done with my work or my life. I believe in a long, creative life, and…I’m moving in that direction! [Laughs.] But when my son arrived five years ago, I thought, “Oh, well, my life just took a turn that I never really expected.” Do you have kids?

I have a daughter, actually.

So you know you had one life up until the day she arrived, and then you had a different life from then on.

And I’m currently entering the next stage, because she’s a teenager now. So, yes, I’m familiar.

[Laughs.] Well, I thought, “Great, this will be my ending: I can round off all the stuff that came before!” And I wanted to tell this tale of the MC5, certainly, from my perspective of being in the eye of the storm. A lot of people have written a lot of things about the band, but I wanted it on the record what it looked like from my perspective as the guy who started the band. And, you know, there’s the ticking of the clock that says, “If you don’t hurry up and write this thing, you might die and miss your chance!”

That’s good incentive.

And ultimately there’s always the possibility of turning straw into gold. The book may be useful to somebody. Someone might find themselves in one of the same positions I was in, and they can see an alternative to the path they’re on.

Regarding the MC5, you and Fred [Smith] obviously knew each other since you were teenagers, since you started the band when you were teenagers, but how did you and he first cross paths?

School. We were schoolmates. I just knew him as one of the kids. And when I wanted to start a band, I was asking around, and one of my friends said, “Hey, you ought to talk that kid Fred. He has a guitar and he plays bongos or something.” And I figured the band could use a bongo player. [Laughs.] And he did have a guitar, and he was a natural player. I had been playing for a few years, so I could show him everything that I knew, and he learned really quickly and became an excellent guitarist himself. I think between the two of us we equaled one whole personality! We fit into each other’s shortcomings and eclectic characteristics.

The MC5 were decidedly harder in tone than most bands of the era. When you were playing the music, did you ever concern yourself with the fact that it might be too hard for people? Or were you just playing how you felt?

No such thing as too hard. We were always striving, because we wanted to put more energy into the music, and sometimes that translated into faster tempos and more volume and a denser tone or timbre. In fact, when I kind of maxed out on Chuck Berry and the contemporary guitar styles of the day, that’s what appealed to me about free jazz: it showed me where to go next, that you could leave the key and the beat behind.

How easy was it for you guys to write songs together? Did it take any time to forge a bond on that front?

You know, it wasn’t that hard, really. And it was great fun. Collaborating and writing songs with people is some of the most fun you can have in music. There’s nowhere I’d rather be than sitting down with someone I like and trying to write songs. So it was great fun, and there was a great sense of accomplishment when you finally end up with something that you think is worthwhile.

I think I discovered you guys on one of the Elektra compilations that came out during the ‘80s, and it was basically a case of “Mind? BLOWN!” An educational experience, to say the least.

Thank you!

Does it surprise you that people are still saying that even now?

Yes and no. We consciously discussed whether our music had historical validity. Meaning, “Would our ideas last over time, or are they just a temporary fashion?” And being that our music was rooted in the core rock ‘n’ roll of Little Richard and Chuck Berry, if we stuck to those basic forms, then the music would sustain itself. I’ll tell you, we did some warm-up dates this summer at some European festivals, and the music holds up perfectly fine. We played for audiences that I’m positive they had no idea who we were, and they loved it.

Hearing you talk about the thought you put into the music, it’s almost like you took your art seriously. What a novel concept.

[Laughs.] We did! We did. We would argue endlessly about if this line was good or if this chord change was good. Yeah, we took it seriously.

When it came time to utter the immortal line, “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” was there any hesitation on your part about dropping the F-bomb?

None. Because my sense was that this was language of everyday usage in America. Everybody used that language, and it was a normal, everyday word. It was colorful and provocative and fit the criteria of a great rock ‘n’ roll song. You know, Elektra Records said that they agreed with us, that the Constitution was on our side, that this was free speech to use this language in an art form. But in the end, they decided against backing our play. [Laughs.] They fired us!

What did you guys think when you first saw or heard about Lester Bangs’ review?

Oh, I was on acid when I read it...and it bummed me out! [Laughs.] I thought, “This is terrible! This guy’s so off the mark… Man, if people believe this… This is not good!” And I took it to heart. And it kind of informed my direction for the band on the next record. I really wanted the next record to prove Lester Bangs wrong, that we could play in tune, that the tempos were going to be solid and the lyrics were going to be good and the melodies were going to be true, and that we were a great rock band. And I probably went a little too far in that direction, but that’s what I was trying to do. And the funny thing about Lester is, of course, that he ended up moving to Detroit, recanting his review, apologizing for it, and becoming a great supporter of the MC5 and one of my best friends until the day he died.

Now that’s a happy ending.

Yeah!

Of course, I’m a critic, so I would say that.

There you go.

Okay, this is just a footnote in the band’s career, but I have to ask about it: in 1972, toward the end of the MC5, the band played in Cambridge, England with Syd Barrett’s post-Pink Floyd band, Stars.

Yeah!

Do you have a recollection of that particular experience?

I don’t, because I was chasing a woman.

Well, that’s a good excuse, though.

[Laughs.] I liked Syd, that’s for sure. And I really dug his guitar playing. But I didn’t hang out to watch him play. I was…otherwise preoccupied.

So when the MC5 came to a conclusion, would you say it was something that happened organically?

Well, yes, in the sense that all things in nature are conceived, born, grow, thrive, flourish, flower, atrophy, wither, and die. [Laughs.] In that regard, the arc of the MC5 follows the arc of almost all other bands. The only difference was that the MC5 had so much more pressure on it than your average rock band. I mean, between the FBI and the U.S. Justice Department and the local and state police agencies and parents and teachers and prosecutors hating us, and pressure from the left, with our own comrades from the left criticizing us, and certainly the conservative right criticizing us. So the MC5 had a lot more wounds and scars to show for it in the end. And we never made any money, we never had any hit records… We paid dues from the day we started until the day we broke up!

After the band broke up, you spent a couple of years not recording, to put it mildly…

Yeah.

Once you got back to the recording business, how did you cross paths with Johnny Thunders?

He came to Detroit with The Heartbreakers, and he asked me to come down to his gig and sit in. And I had just returned from prison and was desperate to get back in front of people and let them know I was in the world, so when he said he wanted to start a band… I knew it would never work, because he was an active opiate abuser, something I had a lot of experience in. But I did it anyway, because I thought I could control it. I thought I was the new, improved Wayne Kramer: “I’ve been to prison, and I know better now!” But I was wrong, again. And, of course, the band never amounted to anything. Because it can’t. You can’t be partners with someone who’s abusing opiates in particular. It’s impossible.

The one thing I did want to ask about your , uh, legally-enforced time in Kentucky was how surreal it was for you to run into [MC5 bassist] Michael Davis while you were there?

Well, it was surreal when I found out that he had a federal case, too. I mean, y’know, I figured, “Okay, I did this to myself and I’m gonna pay a price for it.” And he said, “Yeah, me, too!” [Laughs.] I said, “What?!” Then he got mad at me because I mentioned his case in a newspaper story, so I, uh, don’t talk about him anymore.

I also wanted to ask about the gig you did with guys like Dave Vanian [The Damned] and Lemmy [Motorhead]. That’s one of the greatest guest-star lineups ever.

It was a ball, too. It was really fun, too.

I presume those guys were all just genuflecting.

I don’t know. Maybe. I just looked at them as my co-workers. But it was a step in making peace with the MC5, because we all suffer two deaths: one is the death of our bodies, that we all go through, and then there’s the death of our youth. And some people have this death, and some don’t. And I had it, and I had to kind of reconcile that the band wasn’t going to get back together, and we weren’t going to make everything okay again, and we weren’t going to be the MTV darlings, and that that part of my life had ended, and it was time to move on to my life as a middle-aged man. And the idea of getting back together with Dennis and Michael and playing MC5 music took a little getting used to. We did a whole world tour, and I found that there were aspects of it that I really enjoyed. Even though that band kind of ran out of gas, the idea of still going out and playing MC5 music appealed to me, and that’s how I ended up where I am today. You know, I’m really looking forward to this tour and working with these guys and playing this music for a whole new generation of music fans.

Seeing Don Was’s name in the mix for your band… Until prepping to talk to you today, I hadn’t realized that you were the first guitarist for Was (Not Was).

Yeah! Yep, true story. [Laughs.]

How did you first cross paths with those guys originally?

Don called me up and hired me for a recording session. People call up from time to time and ask me to play on their records. And I went over and met him and his partner, and I started listening to this crazy music that they were composing, and it had so many elements of things that were important to me – free jazz, poetry, atonal ideas – and you could dance to it! [Laughs.] And then they told me they were huge MC5 fans, and their dream was to have Wayne Kramer in their band. And I thought, “Wow, this sounds good to me!” And I loved the cats, and all the other musicians we had were all first-rate Detroit funk masters, and…we had a ball! We still do. I just played with Don last week. It was great.

Another thing I was curious about was the fact that you did some score work for Talladega Nights and Step Brothers. Was it Adam McKay who brought you into those projects?

It was, yes! Do you know Hal Willner?

Absolutely, yeah.

Hal Wilner was the music supervisor on Talladega Nights, and they had another composer who was very good with the orchestra, but he couldn’t rock. [Laughs.] And they wanted aggressive guitar rock for the race scenes. So Hal said, “Well, why don’t you call Wayne Kramer? He lives here!” So they called me up and I went down to the studio, and I watched some of the scenes, and they said, “Do you think you can do this?” And I said, “I’m pretty sure I can!” And then I discovered that Adam McKay and I were really simpatico, that I really enjoyed his company. He’s a brilliant man, politically astute, and we had a lot to talk about. And we became friends, and I count him as one of my best friends today.

I did an interview with him for Vanity Fair last year, and we talked about political stuff in particular. He’s a great guy.

Wait ‘til you see Cheney. [Laughs.] I saw a friends-and-family screening a couple of weeks ago, and it’s killer. It’s really good.

And I’ll just say that when you mentioned Hal Willner, the first thing that came to mind was STAY AWAKE, the Disney tribute, which was where I first discovered him. Any album that features Tom Waits singing “Heigh Ho” from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves is all right in my book.

[Laughs.] Right! Yeah, you know, working for Adam really opened up a lot of doors for me. I was able to get some network jobs and some more feature films. And on occasion, if he feels like I’m the right guy for the job, he’ll hire me for it. He’s a good friend.

Well, to bring it full circle, if you came to the natural conclusion of this book with the arrival of your son, are you already thinking in terms of a sequel?

I am. Yeah, I actually am. Because I enjoyed every aspect of the process. I enjoyed the writing…and as tough as editing is, I enjoyed it! The great Leslie Wells was my editor, and I finally sent her the manuscript, and I had about 140,000 words, and she immediately threw away three chapters! [Laughs.] I said, “But that’s some of my best stuff!” She said, “Wayne, none of it moves the story forward!” Ouch!

Wayne Kramer is on tour now with MC50. Click here for tour dates and tickets.

For more information, click the buttons below: