Interview: Harold Bronson, author of My British Invasion

Interview: Harold Bronson, author of My British Invasion

By Will Harris

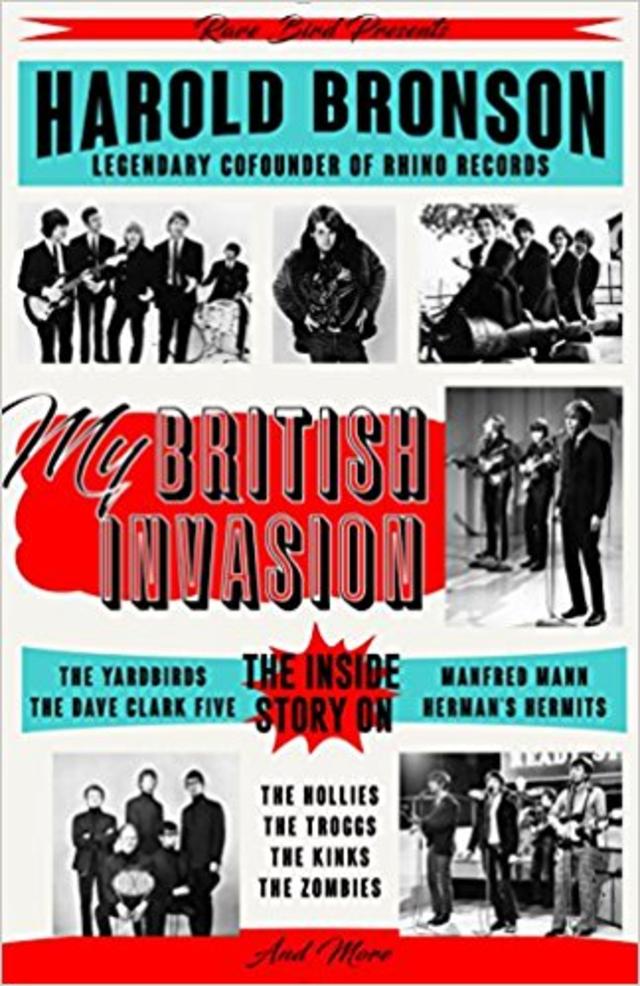

Although it’s appropriate, given that it’s what he’s here to promote, it seems a bit silly to only identify Harold Bronson by the title of his latest book, especially when the identification is being done on the website of the label he helped to found. That’s right: Bronson and his cohort Richard Foos are the guys who started Rhino Records back in 1978, so please follow our lead and genuflect in their general direction.

A few years ago, Bronson wrote a book detailing the origins of Rhino, and now he’s back with a new effort, one filled with just as many music stories - on Herman's Hermits, The Hollies, The Kinks, The Yardbirds, The Troggs, and The Dave Clark 5 - as you’d expect from a man with his background. We hopped on the phone with Bronson and discussed his latest literary endeavor, which is likely to thrill any music fan…and if you’re not a music fan, then why are you reading an interview on Rhino Records in the first place?

As someone with a copy of The Rhino Story sitting on my bookshelf, I was immediately excited to read your new book as soon as I heard about it.

One of the reasons why I wrote The Rhino Story – which I’ve stated before – was that because after Richard [Foos] and I left the company, I think the emphasis was more on profitability and a lot of issues relating to the business, and there was no sort of financial incentive for thinking about the history. So I just thought I should get it down, so if people want to know about the company 10 or 20 years from now, they can go to a library and it’s on the shelf: here’s the history and how it really happened. I also thought it related to the current book: as one gets older, your memory’s not going to get better, right? [Laughs.] So that was another reason for getting it down: preserving the history.

What I was doing at Rhino, as we were reissuing these artists, I was always interested in and it was important for me to respect the labels that had originally put out this product. For instance, when I originally initiated doing our NUGGETS reissue – this was vinyl – the first person I contacted was Jac Holzman, for instance. I’d run things by people. In our relationship with Atlantic Records, it was Ahmet Ertegun. What I’m saying is that it wasn’t just the artists and the hit records that we grew up with. It was also an interest in and a respect for what these other labels had done prior to us.

So sort of a standing-on-the-shoulders-of-giants thing, then.

Yeah!

Did you always have an eye on writing this particular book? In other words, were you setting aside anecdotes while writing The Rhino Story that you wanted to use in this book?

I thought about writing it a little bit the year after I left Rhino, but I was kind of bogged down in the My Dinner with Jimi film. I was doing that, and I was also thinking about films in general at that point, because I’d done a handful. So there was that, and then Simon Fuller wanted to do The New Monkees, so I was kind of focused on that. I just thought that if we did a network TV show, that would be something really interesting, and I could learn what that’s all about. So even though in the back of my head I knew I wanted to do this book, I didn’t really address it right away. In writing it a bit later, the good thing is that I think it turned out better, because I had a little bit more perspective and I had the time to write it. The negative is that there’s been a decline in the book industry, so when my books came out, there was no Borders book chain, for instance. So I think it hurt sales, but ultimately I think the book turned out better by waiting.

In the “My Senior Year” chapter of My British Invasion, you remarked on how great you’d hoped your 21st year was going to be. From what I read, it seems like it turned out swimmingly.

My senior year at UCLA, I was a college rep for Columbia Records. I came to realize that I wanted to work for a major label. I had learned a lot and thought I had the chops to do it. For whatever reason, no label could perceive the potential that I thought I had, which in kind of a roundabout way related to starting the record label in the back room of a record store with Richard. Basically, I liked the concept of turning negatives into positives, and that’s sort of a good example of that.

The book’s particularly fun with the way it provides readers with a fly-on-the-wall feel of the era, with the discussion of the events that were going on at the time, the shows you were going to see, and the albums you were spinning on your turntable that month.

Well, you know, some people have written about periods that they didn’t really experience, but there are a couple of really good books that’ve come out in the past couple of years. One is called 1965 (by Andrew Grant Jackson), and the other is called Fire and Rain: The Year 1970. That’s by David Browne, who writes for Rolling Stone. They’re good books and I recommend them, but they didn’t really grow up with the period, and a lot of times there are certain things that you miss or that pass into culture or history that aren’t correct. So what I wanted to do in that chapter… Well, it’s also subtitled Time Capsule, so as that school year unfolded, I wanted to try and present it, like, “Here’s what I experienced.”

It’s great, because – just to pick an example that particularly struck me – at one point you’re talking about Redbone, a band whose name doesn’t get bandied about a whole lot, and you’re not even discussing one of their best-known songs.

Well, another thing about the book is the Playlists. Most of those records people probably know, but there are some really good records that are relatively obscure. Judee Sill, for instance, or a song called “Hiroshima,”by wishful thinking. I’ll give you “Hiroshima” as an example of how well I was plugged in. I took notice of the song, even though it came out on kind of a smallish label. I think it was…not Imperial Records, but something like that. (It was actually Ampex Records. – Ed.] But it was written by David Morgan, who’d also written the B-side to a couple of singles by The Move. So when this album that nobody had ever heard of came in the office, I kind of said, “Oh, David Morgan, he’s the guy who wrote the B-side of this Move single,” and then it’s, like, “Okay, let me play that.” And it turned out to be a pretty good album!

Just by reading the book, I found myself heading to YouTube and pulling up The Conception Corporation, who – despite being a comedy geek – I’d somehow never heard of. They’re pretty great.

That actually is the ultimate goal that I want to do: by reading about the music, to have people either think, “I haven’t heard this record in three years, let me dig that out and play it, I always liked it,” or in some cases – like yourself – turning people onto things they might not have heard that they might like.

I was actually going to look into who owned the rights to their material, in case it might be something that Rhino could reissue.

Well, actually… [Starts to laugh.] Rhino Handmade put out a double album of material from The Conception Corporation, and I would think that the album sold so poorly that you could probably still get a copy from them! They should still have that somewhere in one of the warehouses…and I’d advise you to get a copy! I was a fan of theirs, as I mention in the book, and they did two albums that sold poorly, but they recorded a third album that was never released. So when we put out the double album, we included that third album.

As far as the British invasion portion of the book, did you walk away with a band that you thought of as the most underrated of the bunch?

That’s a really good question. I know you got the book only a couple of days ago, so I don’t know how much you had a chance to read.

Not as much as I would’ve liked, to be honest. I was only able to make it some between a third and a half of it, unfortunately.

And that’s okay, but – just by the way – as you read further, if you have any other questions or if anything comes up, you know how to get in touch with me. But for instance, one group that I was turned onto at U.C.L.A. was The Move, who – for the most part – nobody really knew of in the US, even though I think they’d had 10 or 11 hits in Britain. So I really couldn’t justify doing a whole chapter on The Move, because I wanted to feature artists that were more familiar to people growing up during that period and had more of a lasting impact. But when I was turned onto The Move, it was a real revelation. By the way, there’s one album of theirs which I do refer to: Shazam. Are you familiar with that album?

I am.

Okay, well, then you know. It’s such a great album, but…I don’t know what it sold in the US, but it’s one of those that, for the most part, most people don’t know about.

I enjoyed reading about Mickie Most. He’s one of those producers who – even though music fans know and appreciate his work – doesn’t seem to get as much mainstream appreciation as he should.

Yeah, I interviewed him in the London 1972 chapter. When I went to London the first time, I thought, “Who can I track down? Who can I interview that never comes to Los Angeles?” And like yourself, I really respected his productions, so I interviewed him, and like with a number of the subjects… A lot of these people from the ‘60s, when I interviewed them in the early ‘70s, they were far past their hit years, and they weren’t really doing much in the way of interviews. So I think I was able to get their stories more, because they really hadn’t been talking. So with Mickie Most, I mean, when you read that chapter, it’s a real revelation, some of the things he was saying. it turned out so well that I pitched it to Rolling Stone. So I wrote it up for them, and I think it was a 2400-word article, a full page.

So from my point of view, other than the time-capsule aspects, on those artist-specific chapters, I think they’re the best overviews on those artists and I think the most accurate. A lot of times when people would write memoirs, and usually someone else actually writes it, the person who writes it, their goal is to get the person’s story down and to put it in a readable form. They’re not paid to tell the subject they’re wrong. They’re not paid to fact-check them. So quite often, as I’ve noticed, whether it’s Graham Nash’s book or Tommy James’s book… There are inaccuracies in a lot of these books. So it was really important for me in these chapters to make these accurate.

I haven’t gotten to it yet, but I’m excited to read the chapter about Status Quo, because – like The Move – they’re another one of those British bands who never really got any due in America.

Yeah, that’s a fun chapter. You’ll enjoy that one. For that one, I interviewed them for Rock Magazine, but since they didn’t really happen in America, they wanted it to be shorter. So all of the stuff on Disneyland wasn’t part of that article and hasn’t been published before.

That begs a question, if one that’s not specifically about the book: what’s your position on the state of music journalism today?

Well, overall, the problem I have with contemporary music, as much as I would like to hear things that I would like, I really don’t. I think part of the problem is that with the popularity of grunge, I think the standards for singers has declined. My son is 25 now, but when he was younger, I would pay attention to the artists that he liked, and I’d take him to see them, but I just would never hear anything that I liked. I was a little bit frustrated. So as far as contemporary music journalism goes, I don’t read much of it, because the music just isn’t something that I can relate to.

When it comes to artists whose work you enjoyed in the ‘60s and ‘70s or whenever, do you still make a point of keeping up with their output?

Usually not. I mean, I was aware more throughout the ‘70s, but…well, again, a lot of it depends. With vocalists, as they get older, their vocals deteriorate. For instance, I’ve heard all the Who albums, and I used to be into Cheap Trick for a number of years after their peak, and I’ve heard most of their albums, if maybe not the last couple. So there are some. But for the most part, the artists covered in the British Invasion book aren’t ones that are still recording.

You’ve also got a chapter where you talk briefly about the Sex Pistols.

Well, just to give you a bit of an overview, I had a good relationship with Johnny (Rotten’s) manager, Eric Gardner, because I’d made the Bearsville deal and brought them into Rhino, and he was and is Todd Rundgren’s manager. So he called me – because he was managing Johnny – about if I’d be interested in making a movie about John’s book (Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs). And I was really kind of surprised, but I asked him, and he said that no one had approached him about optioning it. So I said, “Sure, I want to make a movie!” So the chapter is about describing that whole process and dealing with Johnny, who was –shall we say, and as you probably know – a real character. But it goes beyond that. At the Rhino store, we were big Sex Pistols supporters, and we would sell the imports. And when I wrote for the L.A. Times I did an interview with Malcolm McLaren, and I think I may have had the first article in the U.S. on the Sex Pistols that actually had quotes in it. And you’ll read about it in there, but I was even asked if I wanted to be the bass player in the Sex Pistols after Sid Vicious’s demise. That’s all in the chapter.

I realize this is a spoiler, but…did you seriously consider the offer?

No, because I thought that where they were coming from was too negative. If you think about what they were singing about, and the punk scene in England and how much it was tied into the social condition of the time. So I thought about it for a few seconds, but I just didn’t want to be immersed in that negativity.

Well, on a positive note, the NUGGETS compilations that Rhino released during your tenure were incredibly educational for an aspiring music journalist like myself. Was education part of your intent when you put those collections together?

Oh, yeah. On everything that we did, it was kind of, like, “Okay, here’s the hits, and here are some of the better album tracks, but what are some of the obscurities that we can turn you onto?” Let me give you a good example of that. I compiled nine volumes for Rhino of the best of the British Invasion, so what I did was, on the vinyl I did 14 songs which were, for the most part, the hits that most people knew, and then the bonus tracks on the CD, the six extra tracks, were obscurities that people probably didn’t know. Like, for instance, you’re probably familiar with Amen Corner, but nobody in America knew who they were, even though they had some big hits. So I’d put them on the CD bonus tracks. And people are much more aware of The Creation now, but back then they weren’t, so they’d be a bonus tracks. Or All-Night Stand would be a bonus track. Songs that people didn’t know in America but that I thought were pretty good. So, yeah, I always wanted to turn people onto great music that they might not be familiar with. And that includes this book, with the Playlist section in the back.

Harold's book, My British Invasion, is now available. Grab a copy here.